Akhmim wooden tablets

The Akhmim wooden tablets or Cairo wooden tablets (Cairo Cat. 25367 and 25368) are two ancient Egyptian wooden writing tablets. They each measure about 18 by 10 inches and are covered with plaster. The tablets are inscribed on both sides. The inscriptions on the first tablet includes a list of servants, which is followed by a mathematical text.[1] The text is dated to year 38 (it was at first thought to be from year 28) of an otherwise unnamed king. The general dating to the early Egyptian Middle Kingdom combined with the high regnal year suggests that the tables may date to the reign of Senusret I, ca. 1950 BC.[2] The second tablet also lists several servants and further contains mathematical texts.[1]

The tablets are currently housed in Cairo's Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. The text was reported by Daressy in 1901 [3] and later analyzed and published in 1906.[4]

The first half of the tablet details five divisions of a hekat by 3, 7, 10, 11 and 13. The answers were written in Eye of Horus quotients, and Egyptian fraction remainders, scaled to a 1/320th factor named ro. The second half of the document proved the correctness of the five division answers by multiplying the two-part quotient and remainder answer by its respective divisor (3, 7, 10, 11 and 13).

In 2002 Hana Vymazalová obtained a fresh copy of the text from the Cairo Museum, and confirmed that all five two-part answers were correctly checked for accuracy by the scribe. Typographical errors in Daressy's copy of two problems, the division by 11 and 13 data, were corrected at this time as well.[5] The proof that all five divisions had been exact was suspected by Daressy, but was not proven in 1906.

Contents |

Mathematical content

1/3 case

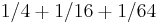

The first problem divides 1 hekat by writing it as 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + (5 ro)(which equals 1) and dividing that expression by 3.

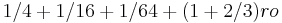

- The scribe first divided the remainder of 5 ro by 3, and determined that this was equal to (1 + 2/3) ro.

- Next the scribe finds 1/3 of the rest of the equation and determines it is equal to

.

. - The final step in the problem consists of checking that the answer is correct and the scribe multiplies

by 3 and shows that the answer is 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + (5 ro), which he knows is equal to 1.

by 3 and shows that the answer is 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + (5 ro), which he knows is equal to 1.

In modern mathematical notation we might say that the scribe showed that 3 times the hekat fraction (1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64) is equal to 63/64 and that 3 times the remainder part ((1 + 2/3) ro) is equal to 5 ro, which is equal to 1/64 th of a hekat.

The other fractions

The other problems on the tablets are computed using a different technique. The scribe uses the fact that 1 hekat = 320 ro and now divides 320 by 7, 10, 11 and 13 to find the required expressions. For instance in the 1/7 computation the division of 320 by 7 gives 45 + 1/2 + 1/7 + 1/14 ro. This is equivalent to 1/8 + 1/64 hekat + (1/2 + 1/7 + 1/14) ro. Checking the work required the scribe to multiply this equation by 7 and showing that the result was 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + (5 ro) again.

Accuracy

The computations show several mistakes. For instance in the 1/7 computations  is said to be 12 and the double of that 24 in all of the copies of the problem. The mistake takes place in exactly the same place in each of the versions of this problem, but the scribe manages to find the correct answer in spite of this error. The fourth copy of the 1/7 division contains an extra error in one of the lines. The mistakes made suggest that the scribe may have been carelessly copying the problems from some other source.

is said to be 12 and the double of that 24 in all of the copies of the problem. The mistake takes place in exactly the same place in each of the versions of this problem, but the scribe manages to find the correct answer in spite of this error. The fourth copy of the 1/7 division contains an extra error in one of the lines. The mistakes made suggest that the scribe may have been carelessly copying the problems from some other source.

The fraction 1/11 computation occurs four times and the problems appear right next to one another leaving the impression that the scribe was practicing the computation procedure. The 1/13 computation appears once in its complete form and twice more with only partial computations. There are errors in the computations, but the scribe does find the correct answer. The 1/10 computation is the only fraction computed only once. There are no mistakes in the computations for this problem.[5]

Hekat problems in other texts

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus contains several examples of hekat division. The problems are somewhat different in nature but the expression of measures of grain in terms of Horus eye fractions of the hekat and remainders in terms of ro appear in several problems. Some examples include:

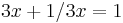

- Problems 35-38 in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus find fractions of the hekat. The problems in this section are equivalent to what we now call linear equations. Problem 35 for instance can be restated as

, what is x? The answer is first computed to be 1/5 + 1/10 hekat. This is rewritten as a Horus eye fraction by multiplying 1 hekat = 320 ro by (1/5 + 1/10) giving 96 ro. This is determined to be (1/4 + 1/32 + 1/64) hekat + 1 ro. This fraction is multiplied by (3 + 1/3) to check that this really gives 1 hekat.[6]

, what is x? The answer is first computed to be 1/5 + 1/10 hekat. This is rewritten as a Horus eye fraction by multiplying 1 hekat = 320 ro by (1/5 + 1/10) giving 96 ro. This is determined to be (1/4 + 1/32 + 1/64) hekat + 1 ro. This fraction is multiplied by (3 + 1/3) to check that this really gives 1 hekat.[6] - Problem 47 provides a list of fractions of 100 hekat.

- Problem 80 gives 5 short tables listing Horus eye fractions of the hekat and the equivalent regular fractions as well as expressions in terms of another unit called the hinu.[6]

The Ebers Papyrus is a famous late Middle Kingdom medical text. Its raw data was written in hekat one-parts suggested by the AWT, handling divisors greater than 64.[7]

References

- ^ a b T. Eric Peet, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 9, No. 1/2 (Apr., 1923), pp. 91-95, Egypt Exploration Society

- ^ William K. Simpson, An Additional Fragment from the "Hatnub" Stela, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 20, No.1 (Jan 1961), pp. 25-30

- ^ Daressy, Georges, Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, Volume No. 25001-25385, 1901.

- ^ Daressy, Georges, "Calculs égyptiens du Moyen Empire", in Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes XXVIII, 1906, 62–72.

- ^ a b Vymazalova, H. "The Wooden Tablets from Cairo: The Use of the Grain Unit HK3T in Ancient Egypt." Archiv Orientalai, Charles U., Prague, pp. 27–42, 2002.

- ^ a b Clagett, Marshall Ancient Egyptian Science, A Source Book. Volume Three: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society) American Philosophical Society. 1999 ISBN 978-0-87169-232-0

- ^ Pommerening, Tanja, "Altagyptische Holmasse Metrologish neu Interpretiert" and relevant pharmaceutical and medical knowledge, an abstract, Phillips-Universtat, Marburg, 8-11-2004, taken from "Die Altagyptschen Hohlmass" in studien zur Altagyptischen Kulture, Beiheft, 10, Hamburg, Buske-Verlag, 2005

Other:

- Gardener, Milo, "An Ancient Egyptian Problem and its Innovative Arithmetic Solution", Ganita Bharati, 2006, Vol 28, Bulletin of the Indian Society for the History of Mathematics, MD Publications, New Delhi, pp 157–173.

- Gillings, R. Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs. Boston, MA: MIT Press, pp. 202–205, 1972. ISBN 0-262-07045-6. (Out of print)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Akhmim Wooden Tablet" from MathWorld. Scaled AWT Remainders

- http://www.whonamedit.com/synd.cfm/443.html